Featured below are some excerpts from the book Oblique Drawing, A History of Anti-Perspective by Massimo Scolari. This scholarly and fascinating work is a must if you'd like to take real plunge into the more ethereal realms of perspective and projection. If you have ever thought the topic of perspective was boring, toss a little mysticism and philosophy into the pot and stir well.

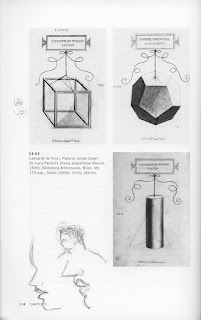

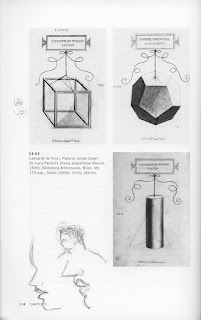

"Scolari's generously illustrated studies show that illusionistic perspective is not the only, or even the best, representation of objects in history; parallel projection, for example, preserves in scale the actual measurements of objects it represents, avoiding the distortions of one-point perspective. Scolari analyzes the use of nonperspectival representations in pre-Renaissance images of machines and military hardware, architectural models and drawings, and illustrations of geometrical solids. He challenges Panofsky's theory of Pompeiian perspective and explains the difficulties encountered by the Chinese when they viewed Jesuit missionaries' perspectival religious images.

Scolari vividly demonstrates the diversity of representational forms devised through the centuries, and shows how each one reveals something that is lacking in the others." [source]

Plotinus and the Problem of Depth

The works of Plotinus were collected in fifty-four treatises and arranged in six Enneads, of which the first and the fifth deal with aesthetic problems. For Plotinus, an image was the reflection of the thing that, in accordance with the Stoic principle of universal sympathy, shared the same nature as its model. The purpose of an image was not merely to reproduce the appearance of an object, but rather, to understand the nous, the intellect, and through it the universal soul. Yet the necessarily abstract images of art are meant neither to pique aesthetic pleasure nor imitate the appearance of reality nor provide moral teachings. Plotinus therefore found it necessary to establish the conventions today known as the statutes of representation. They stated that to achieve knowledge of the nous, the observer had to be acquainted with the physical nature of vision: this was the only way to perceive the message of the work correctly. In considering the problems of vision, in particular the reduction of distant dimensions and the weakening of color in distant objects, Plotinus claimed that the only view faithful to the true sizes and tones of color was the one very close to the eye, which represented the object in its completeness. Only this view made it possible to see things in detail and correctly assess measurements and overall size. Distant objects were indeterminate and thus imperfect; all objects therefore had to be represented in the foreground, in the very fullness of light, with exact colors, and in all their detail and without shadows. This meant avoiding depth, since depth entailed shadow or obscurity and thus empty matter. According to Plotinus, the eye had to become "equal and similar to the object observed in order to contemplate one can never see the sun without becoming similar to it, and a soul can never contemplate beauty without being beautiful itself." This form of interpenetration was not possible with the "eye of the body" but only with the "inner eye." The importance of this claim is obvious: when seventeenth century optics correctly resolved the geometrical problem of vision.

it found that the "eye of the body" was only a channel of vision and that perception really began from the retina: what can really see is the "inner eye."

Similar arguments were advanced by mystics before Plotinus and by Christian theologians after him, but his claims are important because they were applied to the problem of representation. They implied that the space between the observer and the object was annulled, and thus also the point of view. Plotinus said that "there is no point at which one can fix one's own limits and say: this is as far as I am up to here." He claimed that perception "clearly takes place where the object is... to see, it is necessarv to lose consciousness of one's own being, it is necessary in some way to stop seeing."

Plotinus's ideas did not have a direct influence on the painting of his day, but they certainly affected representation up until the Middle Ages. Their anti-perspectival characteristics, together with their breadth of philosophical conception, allow us to extend the symbolic scope of the limits that fourteenth-century optics put on fifteenth-century painting. At the same time, it is worth pointing out that parallel projection should have avoided the formation of depth by avoiding convergence, leaving aside the Euclidean "eye of the bodv." It would have been possible to see the geometry of real measurements and understand how the "eve of the sun" was bound to represent it without shadows. The fact that this happens beyond vision is what Plotinus described as "becoming equal and similar to the object." From the fifteenth century onward, the inner eye, freed of its fixed mysticism and the symbolic insularity of painting, moved to become the place of exact knowledge, where measurement shatters, the seduction of the gaze. [pg.16-17]

Giuseppe Castiglione, 1757, Handscroll of the Qianlong Emperor receiving tribute horses from Tartar envoys*

"But given the Chinese disinclination for generalist laws and theorizing tangible demonstrations were necessary in order to convince them that perspective was the right way to see and therefore to represent: in short, the right way to think. Sight and thought had to converge in harmony toward that magical point where the parallel lines met and where the Western painting tradition placed the image and the idea of the divine infinite. Nineteen years after Rice's death, the Jesuit Francesco Sambiaso published a book on perspective titled Risposte alle questioni sul sonno e sulla pittura (Replies to questions on sleep and on painting), and later Father Buglio presented the Emperor with three paintings that exemplified the rules of perspective.

But if the victory of European astronomy was total and was accepted by the Chinese for practical reasons as the best method for ordering those rites that objectified their relationship with the heavens, the Emperor, and his subjects, the same did not happen with painting. Perspective was certainly "marvelous" but that did not make it better than traditional methods of painting, and the Chinese understood that its seduction concealed a "conversion" that had not been asked for and that conflicted with the attributes of the Emperor, who was both mother and father of his subjects. Resistance to perspective was thus very tenacious, and although they made use of it, even those painters who had converted to Christianity remained substantially bound to traditional Chinese painting. The attempts to acquaint the Chinese with the rules of perspective continued, however. In 1729, the greatest painter who worked in China, Giuseppe Castiglione, arranged for the translation and publication of the fundamental work of his teacher Andrea Pozzo." Though this attempt was met with little success, Lastiglione was, along with Verbiest, one of the seven Jesuits elevated to the status of Mandarin between 1581 and 1681. and therefore he played a role of some prestige at the imperial court. In the end it was the rigidity of the Confucian China of the Mandarins and literati, seduced by science and by the dignity of Rice's life at the end of the Ming Dynasty, as well as by Castiglione atterward, that managed to colonize the colonialists" [pg.144]

*Note: Giuseppe Castiglione (1688 – 1766), was an Italian Jesuit brother and missionary in China, where he served as an artist at the imperial court of three Qing emperors – the Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors. He painted in a style that is a fusion of European and Chinese traditions.

Comments